Home Written

Heinlein’s 1961 novel “Stranger in a Strange Land” contains one of the most influential sci-fi stories of the previous century. The protagonist is Valentine Micheal Smith, a man that was raised by aliens on Mars. The story starts when he returns to Earth and is confronted with human culture. Especially the second half of the book is kind of controversial (Spoiler alert: Micheal founds a sex cult that gives you magical powers), but the book nonetheless contains a lot of interesting concepts that were ahead of its time. The most influential of which is probably the Martian word “grok”.

Grok is frequently used by Micheal (and Martians in general). But Micheal can’t give a good explanation of its meaning; it’s an untranslatable word. Eventually, we learn that the literal meaning of the Martian word is “to drink”. However, the term is used in a much broader way. Drinking is a metaphor for a kind of absorption of knowledge. Hence it might be better to translate it as “to understand” or “to embrace”, but the book emphasizes that grokking is a deeper concept than understanding. It is a central concept in Martian culture. Some passages from the book:

Grok means “to understand,” of course, but Dr. Mahmoud, who might be termed the leading Terran expert on Martians, explains that it also means, “to drink” and “a hundred other English words, words which we think of as antithetical concepts. ‘Grok’ means all of these. It means ‘fear,’ it means ‘love,’ it means ‘hate’—proper hate, for by the Martian ‘map’ you cannot hate anything unless you grok it, understand it so thoroughly that you merge with it and it merges with you—then you can hate it. By hating yourself. But this implies that you love it, too, and cherish it and would not have it otherwise.

‘Grok’ means to understand so thoroughly that the observer becomes a part of the observed—to merge, blend, intermarry, lose identity in group experience. It means almost everything that we mean by religion, philosophy, and science and it means as little to us as color does to a blind man.

However much Heinlein wants to cover the definition of the word in a shroud of new-age mystery, the meaning of a word is a function of its usage, not its definition. Hence, I would like to try to empirically evaluate its functional meaning, by using BERT.

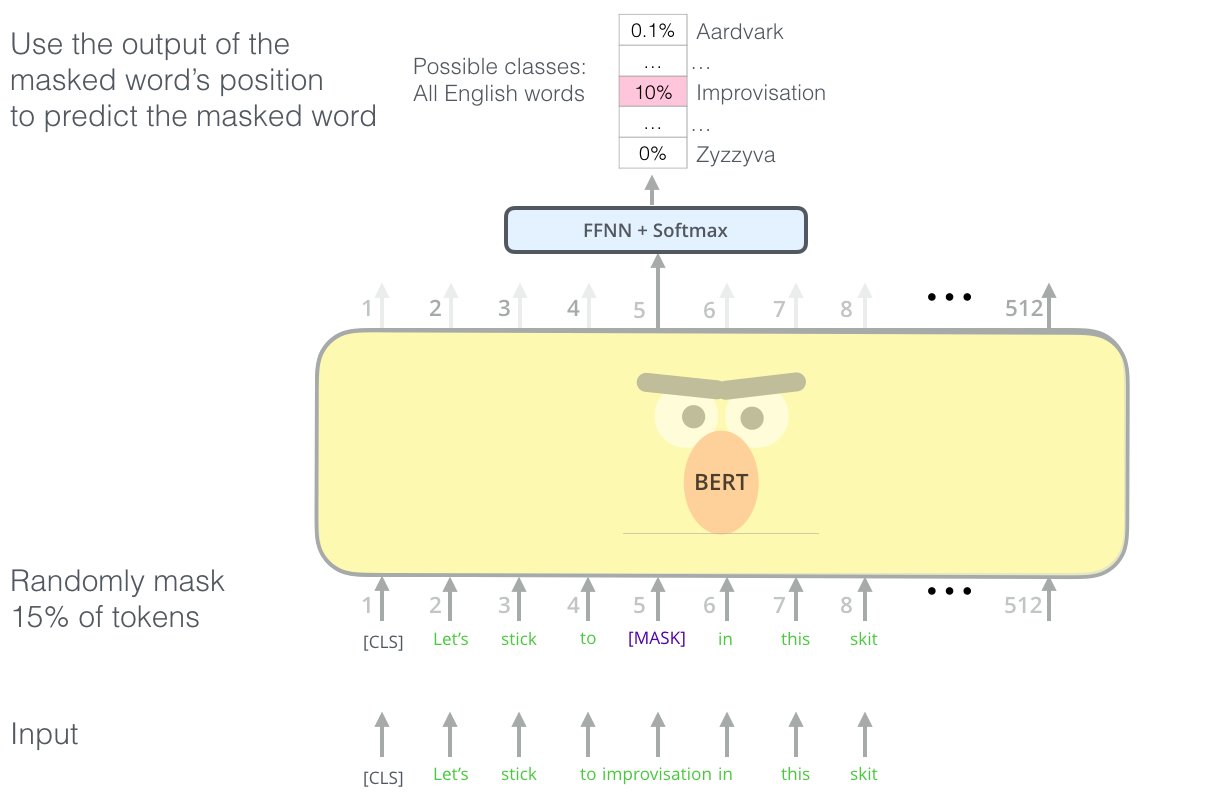

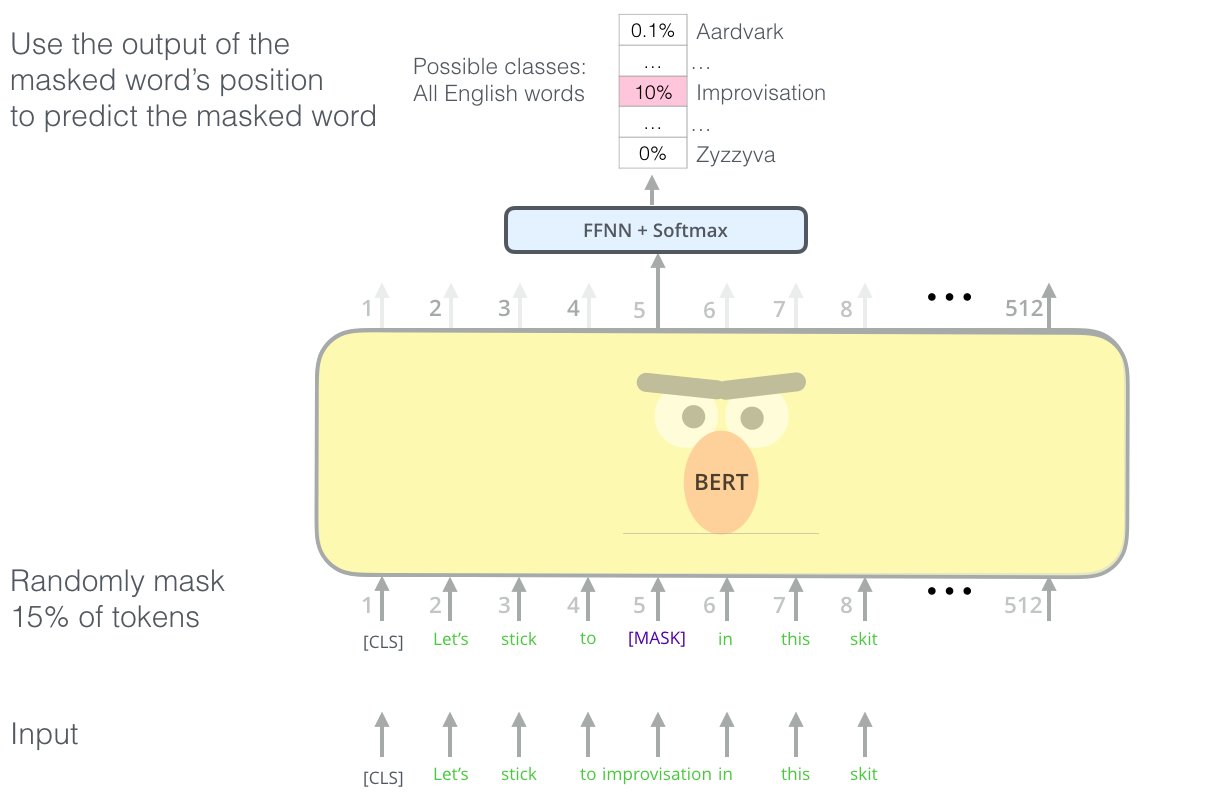

BERT is a masked language model, meaning that it predicts the likelihood of a word appearing in a given context.

This allows to approximate what English words are used most similarly to “grok”. For example, if we mask grok in the following context:

“But, Jubal, don’t make a suggestion like that to Mike. He wouldn’t [MASK] that you were joking - and you might have a corpse on your hands.”

BERT’s top 2 predictions are: “believe” and “understand”.

We can get a more complete picture by averaging the results for all

the 305 occurrences of grok in “Stranger in a strange land” (the

original, uncut version). These predictions were generated using the

pre-trained huggingface model called roberta-large (a

variant of BERT).

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| know | 11.67% |

| understand | 10.96% |

| think | 7.28% |

| see | 3.73% |

| do | 2.78% |

| get | 1.48% |

| believe | 1.39% |

I only included the words that have probabilities above 1.2%. We can repeat the same exercise with “grokked” (102 occurrences):

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| knew | 7.07% |

| understood | 6.90% |

| saw | 4.29% |

| realized | 3.01% |

| thought | 2.72% |

| felt | 2.24% |

| learned | 2.03% |

| seen | 1.99% |

| known | 1.59% |

Reassuringly, these give very similar results. Lastly, let’s check the results for “grokking” (44 occurrences):

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| it | 3.91% |

| understanding | 3.46% |

| learning | 2.98% |

| living | 2.35% |

| shape | 1.89% |

| shape | 1.47% |

| moment | 1.33% |

| natural | 1.31% |

| doing | 1.29% |

| meaning | 1.22% |

The results of “grok” and “grokked” largely seem to agree with the definition in the Merriam-Webster dictionary: “to understand profoundly and intuitively”. Especially so for the past tense. Only in the decomposition of “grokking” do we get any hint of a more mystical component. The active form of “grok” is related to e.g. “living”, “shape” and “moment”. Note furthermore that the absolute probabilities for the best predictions are much lower. This is what you would expect if there is no single English word with a consistent match.

As a kind of control, I checked what the model predicts for regular English words. If there are enough occurrences, the model predicts the word itself by quite a large margin, followed by some related words. For example, using “have” (1062 occurrences).

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| have | 77.36% |

| ’ve | 4.03% |

| need | 1.52% |

| get | 1.32% |

Or for “understand” (85 occurrences)

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| understand | 36.75% |

| know | 11.70% |

| see | 4.52% |

| get | 3.81% |

| hear | 3.05% |

| believe | 2.40% |

Notice that, especially when getting to the bottom of the table, there start to appear entries that have less to do with “understand”, like “hear”. It’s important to remember the semantics of this table. It’s “can be used in the same context”, not “means the same thing”. Of course, as the context length increases in size, and if the models are accurate enough, these should largely converge. But alas, current models and context sizes are not perfect. As an example, observe the output for “first” (245 occurrences).

| word | probability |

|---|---|

| first | 53.93% |

| last | 2.54% |

| next | 1.52% |

| second | 1.18% |

Although it rightly guesses “first” with a big margin, the next entries are not synonyms at all. Let’s take an example from the book:

Meet me at the desk; I’ll be paying the bill.” She left very suddenly.. . They went to the town’s station flat and caught the [MASK] Greyhound going anywhere.

Observe how in this case, both “first”, and “next” are completely sensible options. There is not enough context to decide. This explains why for “grokking”, “it” is the first option. It can be used as a generic placeholder for a word if there is no better alternative. Similarly, “get” occurs quite often.

All source code can be found in this

colab notebook. To replicate you only need to upload “Stranger in a

strange land” in the epub format and rename it book.epub.

Next, you can just run all cells.